The Art and Science of Earn-Outs in M&A

I. Introduction | Why Use an Earn-Out?

Amid the relatively high interest rates and accompanying M&A slowdown of recent years, it has become more popular—or at least more visible—for buyers and sellers across sectors to take a page from the life-sciences playbook and consider structuring their M&A transactions to include an earn-out.

An earn-out is a mechanism to provide for contingent additional consideration based on a target’s post-closing performance.

Earn-outs can offer several advantages to both buyers and sellers in an M&A transaction. They can:

- Help deal with uncertainty or volatility in the target’s revenue, earnings, or growth prospects, especially in emerging or disruptive sectors or markets;

- Align the interests and expectations of sellers and buyers and incentivize sellers to remain involved and committed to the target’s post-closing operations while avoiding the use of rollover equity;

- Reduce the upfront payment requirements for buyers and provide a mechanism for them to share the upside or downside of the target’s performance with sellers; or

- Resolve valuation gaps between the parties, especially when there is a lack of comparable transactions or reliable projections.

While earn-out provisions may seem to be an attractive solution to the problem of pricing a transaction in an uncertain economy, they are typically bespoke, highly negotiated, and can lead to disputes if not carefully structured.

Often, disputes resulting from earn-out provisions mean that the parties’ negotiations over price are effectively only postponed until after closing. In Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster of the Delaware Court of Chancery words: “an earn-out often converts today’s disagreement over price into tomorrow’s litigation over the outcome.”[1] In addition, as a rule of thumb, the more money allocated to an earn-out relative to the upfront purchase price and the longer the duration of the earn-out period, the more likely it is that a dispute will arise.

The current landscape, influenced by market volatility, post-pandemic considerations, and recent case law, demands a nuanced understanding of earn-out provisions and an appreciation of how they may work in practice.[2]

II. What’s Market?

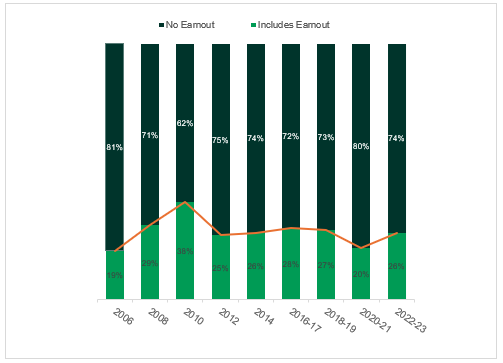

A. Frequency

Traditionally, earn-outs have been heavily utilized in the life sciences sector, where the value of a target company may depend on the outcome of clinical trials, whether (and when) regulatory approvals are received, sales of a drug or device, or a combination of these. Private pharmaceutical industry transactions in particular have employed earn-outs in over 80% of transactions in recent years.[3]

By contrast, close to one in five private transactions outside the life sciences sector utilized an earn-out over the past decade.[4] According to recent analyses, outside the life sciences sector, the use of earn-outs rose from 15% in 2019 to a high of 30–37% in 2023, before settling back to approximately 22% in 2024.[5]

Source: American Bar Association, 2023 Private Target Mergers and Acquisitions Deal Points Study

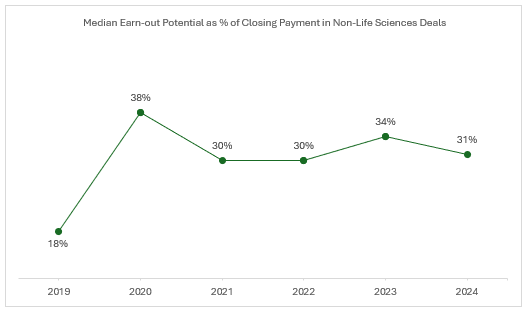

B. Size

The median size of earn-out transactions outside the life-sciences sector was 31% of closing payments (including escrowed amounts) in 2024, down from 34% in 2023 and up from 30% in 2022.[6]

Source: SRS Acquiom 2025 M&A Deal Terms Study.

By contrast, in the life sciences sector, the median earn-out payments were approximately 61% of total consideration, reflecting the sector’s heavy reliance on post-closing milestones to bridge the value gap and allocate risk of future performance.

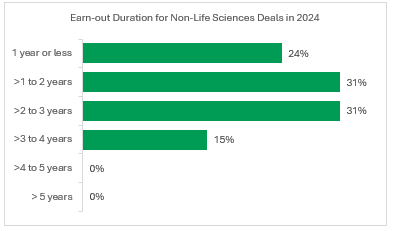

C. Duration

The median length for the earn-out performance period for transactions outside the life sciences sector is 24 months. By contrast, in addition to allocating a higher proportion of the purchase price to earn-out payments, life-sciences sector transactions also typically utilize longer earn-out periods (e.g., 3–5 years or more).

Source: 2025 SRS Acquiom M&A Deal Terms Study

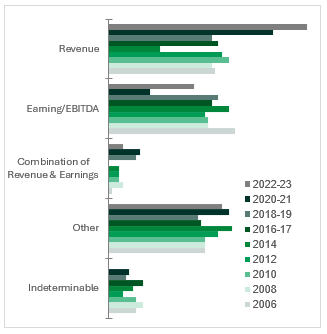

D. Metrics

Most earn-outs are structured with financially-based metrics, with revenue as the most popular metric, followed by earnings or EBITDA. Recently, earn-outs have become more complex, often incorporating multiple metrics that include both financial and non-financial benchmarks tied to the target’s business. These may involve factors such as customer retention or, especially in the energy sector, the price of an underlying commodity. In some cases, earn-outs are structured around more specific or objective milestones, such as the satisfactory completion of clinical trials or the receipt of regulatory approvals.

When negotiating financially-based earn-out metrics, the parties’ preferences typically diverge based on their economic interests and control over post-closing operations. Sellers generally favor revenue-based targets, which are top-line, and less vulnerable to manipulation through changes in cost structure or accounting treatment. Buyers, by contrast, typically prefer net income or EBITDA-based targets, as these reflect the actual profitability and value derived from the business. Among these, EBITDA often emerges as a compromise: while it includes operating costs (unlike revenue), it excludes non-operational items like interest, taxes, and depreciation, making it less prone to subjective adjustments than net income. For this reason, EBITDA-based milestones are common in negotiated outcomes, balancing sellers’ desire for fairness and predictability with buyers’ focus on financial rigor and value capture.

Source: American Bar Association, 2023 Private Target Mergers and Acquisitions Deal Points Study.

E. Post-Closing Covenants.

When a transaction includes an earn-out, the seller’s ability to receive earn-out payments depends on the performance of the target company or acquired business over a period of time after the closing. Sellers typically press for a series of post-closing covenants relating to actions that buyers will or will cause the target company or business to take, or refrain from taking, after the closing in order to protect the seller’s potential earn-out payments. Buyers, on the other hand, generally will resist post-closing covenants or other rights and restrictions that interfere with their ability to operate the target company or business during the earn-out period, particularly any obligations requiring them to take certain actions to achieve or maximize the earn-out.

These post-closing covenants will vary depending on the level of integration, autonomy, and control of the target company or acquired business by the buyer following the closing. However, sellers usually try to negotiate for certain covenants, including covenants that a buyer will:

- operate the target company or acquired business consistent with past practice or, in some cases, in accordance with an existing business plan;

- use commercially reasonable efforts to achieve the earn-out;

- avoid actions, or not take actions in bad faith, that would materially impair or interfere with achievement of the earn-out;

- run the target company or business as a stand-alone entity or division;

- maintain separate books and records for the target company or business and provide the seller with access to these;

- maintain a minimum amount of working capital of the target company;

- not incur any new debt or debt in excess of a specified amount; and

- not dispose of any portion of the target company or business.

According to the latest ABA Private Target Mergers & Acquisitions Deal Points Study[7], which reviewed transactions involving a private target between 2022 and Q1 2023, 25% of the transactions that included earn-outs contained at least one of the following post-closing covenants: (1) a covenant to run the business consistent with past practice, (2) a covenant to run the business to maximize the earn-outs or (3) a covenant to run the business as a stand-alone entity or division. 8% contained at least two of these post-closing covenants, and 58% contained some other language protecting the seller’s right to the earn-out, including commercially reasonable efforts provisions, covenants against bad faith actions, and restrictions on new debt.

F. Disputes

As the use of earn-outs has grown, so too has the frequency of post-closing disputes related to them. According to a recent study,[8] the number of dockets mentioning “earn-out” and “M&A” filed in federal and state courts in the first quarter of 2023 almost doubled compared to the same period of the previous year. This data provides a snapshot, though we note that the first quarter of 2023 had an exceptionally high number of dockets mentioning “earn-out” and “M&A.” It also is important to note that many earn-out disputes are resolved privately, suggesting that disputes regarding earn-outs are more prevalent than the case dockets suggest.

III. Recent Guidance from Delaware.

From a procedural standpoint, earn-out provision ambiguity can be especially problematic in Delaware, where such ambiguity often leads to a factual inquiry for a jury during a trial. In the past few years, the Delaware Chancery Court, the leading jurisdiction for M&A transactions in the United States, has adjudicated several earn-out disputes. These recent decisions reaffirm that the court will enforce bespoke earn-out provisions as written. We summarize the most salient points arising from these decisions below.

A. Clearly Defined Milestones

Earn-out payments are typically triggered by events or targets that occur after the closing of the transaction, often called milestones. A typical earn-out provision might call for payment once the purchased product receives regulatory approval, if the company achieves a certain EBITDA or other financial target, or a combination thereof.

If milestones are not clearly defined, however, the parties may end up disputing whether or not a milestone was achieved.

In Fortis Advisors v. Dematic Corporation,[9] buyer-defendant acquired the seller-plaintiff’s hardware and software solutions business. The merger agreement required the defendant to make contingent payments if the company achieved certain performance targets. The targets were based on EBITDA calculations and sales of “Company Products.” The merger agreement, however, did not clearly define the term “Company Products,” nor did it cover a scenario in which the buyer integrated the products manufactured by the acquired business into its existing products.

When the earn-out was not achieved, the parties disagreed on whether “Company Products” included products made by integrating the acquired business’ software and other know-how into the buyer’s products.

After considering the surrounding circumstances, the court accepted the seller-plaintiff’s view that “company products” included software developed after the merger that made use of the seller’s purchased source code and entered a multimillion-dollar judgment in favor of the seller.

|

Lessons from Case Law: Define the earn-out metrics or milestones as clearly and objectively as possible

Earn-out provisions should be carefully drafted to ensure specificity and clarity. Parties should set out standards for determining milestone achievement and measurement of metrics of the earn-out terms that do not leave room for subjective interpretation. The language should be bespoken to the unique business context and circumstances involved. This may include examples in-line or as schedules for clarity. They should avoid ambiguous or vague terms that could lead to interpretation or calculation disputes. It is essential to involve not only in-house and outside legal counsel but also the business team, accountants and tax advisors. In addition, to provide a framework for interpretation and minimize potential ambiguities, parties may consider including general statements of intent regarding the earn-out or illustrative examples within the agreement. |

B. “Efforts” Obligations

Parties should consider whether (and how) to define “efforts” obligations.

Upon the closing of an M&A transaction, when a buyer assumes ownership of a business, they often implement changes to operations, strategic direction, capital investments, or take other actions that typically alter the acquired company’s financial performance and, consequently, its ability to meet earn-out targets. Therefore, post-closing adjustments can be a source of disagreement and legal action.

To minimize this risk, careful contract language should outline the buyer’s decision-making authority in respect of the target or acquired business and how post-closing modifications will affect the earn-out calculation. This upfront clarity can reduce misunderstandings and potential disputes.

In Menn v. ConMed Corp.,[10] the parties agreed to an earn-out structure where the buyer committed to pay the sellers USD1.25 million up front, to make milestone payments of up to a total USD10.25 million upon the product’s achievement of four development objectives, and to make earn-out payments of USD2 million upon the first sale and in the amount of 10% of the net sales generated for a period after the first sale.

The buyer also agreed to use “commercially best efforts” to maximize these milestone and earn-out payments. Additionally, the seller had the right to accelerate earn-out payments if the buyer ceased development or sales, except when cessation was due to safety concerns.

Post-closing, the buyer made 87.8% of the potential earn-out payments but discontinued the product after encountering safety issues. The seller subsequently sued to obtain the remaining earn-out payments.

In considering whether the buyer had complied with its obligation to use commercially best efforts to maximize the milestone and earn-out payments, the court outlined the framework for analyzing a post-closing “efforts claims”, focusing on whether the person obligated to use its efforts had reasonable grounds for its actions and sought proactively to address issues. The court provided examples of breaches of efforts obligations, including: (i) failing to collaborate with the counterparty to solve problems, (ii) using an inadequately sized sales force to achieve milestones, or (iii) submitting false data and refusing to cooperate with regulators.

Applying this standard, the court found no evidence that the buyer breached its obligation to use commercially best efforts. This conclusion was reached, in part, because the evidence showed the buyer dedicated highly qualified employees to address how the product could be re-designed to be safer, and the ability to redesign the product for safety reasons was expressly incorporated into the operative agreement. The court concluded that the redesign efforts demonstrated the buyer’s compliance with its “commercially best efforts” obligation.

In Pacira BioSciences v. Fortis Advisors,[11] a buyer claimed that the seller interfered with its business decisions in an effort to ensure that an earn-out payment would be triggered. The earn-out was due only if the buyer obtained a specific reimbursement rate from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid for one of its medical devices. To ensure that the buyer achieved the milestone, the seller reached out to the buyer’s employees to demand action and contacted the regulator to advocate for the reimbursement rate. Although the M&A agreement gave the buyer the right to operate the business “in its sole discretion,” the court held that it imposed no limitation on the seller’s ability to contact employees or regulators.

The case Neurvana Medical v. Balt USA[12] presented the opposite scenario: there, a buyer failed to meet an earn-out milestone despite numerous offers of assistance from the seller. As a result, the seller claimed that the buyer had interfered with the seller’s right to receive an earn-out payment. The court disagreed because the buyer had “sole discretion” over “all matters relating to” the product and while the seller was entitled to offer assistance, the buyer had no obligation to accept it.

|

Lessons from Case Law: Earn-out-related covenants should be crafted with specificity to minimize potential disputes.

Specify the duration, frequency, and timing of the earn-out payments, and provide for adequate reporting and verification: Regularly scheduled payments or payments scheduled upon specific events or milestones can provide assurance between the parties and provide an earlier flag for any potential disputes. An agreement should require reporting of important data or information, and it should allow commercially reasonable means for verifying the information provided. Parties should consider including specific covenants that address critical aspects of the acquired business’s operations, earn-out targets, or areas prone to manipulation including whether a buyer must retain certain employees, continue specific past practices, including discounts and training, and fund future improvements or development. Rather than debating what constitutes “reasonable” efforts, some parties opt for a simpler solution: the buyer commits to invest a specific dollar amount in product development. Once spent, the buyer has satisfied its earn-out obligations, regardless of whether milestones are achieved. This approach offers clear advantages. Compliance is objective (funds spent or not), litigation risk drops dramatically, and both parties have certainty about their obligations. It works particularly well in pharmaceutical and medical device contexts where development costs are predictable. Buyers typically insist on “escape hatches” allowing them to cease funding if material health or safety issues arise, significant IP challenges emerge, or a superior competitive product enters the market. By replacing subjective “efforts” standards with objective funding commitments, parties can avoid many of the disputes that plague traditional earn-out structures while still providing sellers with meaningful assurance that their product will receive adequate investment post-closing. |

C. Use of Outward-Facing and Inward-Facing Commercially Reasonable Efforts Standard

One aspect of structuring an earn-out is defining the level of efforts (if any) that the buyer is required to devote to achieving the earn-out. Generally, buyers prefer that the express contractual terms permit them to manage the business post-closing in its sole discretion, while sellers typically seek, among other things, to require buyer to devote a certain level of “efforts” to achieve the milestones. The parties may define the required efforts by requiring the buyer to use the same level of efforts that similar industry participants would use for similar products under similar circumstances (sometimes called an “outward-facing” efforts obligation), or may require the buyer to use a level of efforts that the buyer would use in developing, marketing or selling its own similar products (sometimes called an “inward-facing” efforts obligation). Typically, the outward-facing standard is considered more seller-friendly, because the seller can measure the buyer’s efforts by reference to third parties, and the inward-facing standard is seen as more buyer-friendly as the buyer’s efforts are measured against its own past practice in similar situations. However, in practice the reality is more complex due to the highly customized nature of earn-out provisions.

- Outward-facing. In Shareholder Representative Services LLC v. Alexion Pharmaceuticals,[13] buyer Alexion acquired Syntimmune, a biopharmaceutical development company focused on drugs to treat autoimmune diseases, for USD400 million in cash upfront at closing, and up to USD800 million in possible additional earn-out payments tied to achievement of certain milestones relating to the development and commercialization of a monoclonal antibody, ALXN1830. The parties’ agreement required that Alexion use commercially reasonable efforts to develop ALXN1830 to satisfy specified milestones, with commercially reasonable efforts measured by reference to efforts and resources typically used by biopharmaceutical companies similar in size and scope to Alexion for the development and commercialization of similar products at similar development stages and taking into account other relevant factors. During the earn-out period, Alexion was itself acquired by another pharmaceutical company, which then subjected all of Alexion’s programs to review, including ALXN1830. In this case, the court determined to evaluate Alexion’s efforts by reference to a hypothetical similarly situated company. The court observed that the relevant efforts standard did not permit Alexion to consider its own self-interest in determining what is commercially reasonable. While Alexion’s obligation did not require that it act in a manner that would otherwise be contrary to prudent business judgment, Alexion’s decision to terminate the development of ALXN1830 was driven largely by pursuit of merger synergies, and the court concluded that termination of ALXN1830 fell short of the typical efforts a hypothetical company similarly situated to Alexion would have devoted to the program.

- Inward-facing. In Fortis Advisors v. Johnson & Johnson, [14] buyer Johnson & Johnson (“J&J”) acquired Auris Health, Inc. (“Auris”), a privately-held developer of robotic technologies, for USD3.4 billion in cash upfront at closing, with the potential for up to an additional USD2.35 billion in earn-out payments tied to achieving certain milestones related to the development of Auris’s surgical robots. Among other things, the parties’ agreement required that J&J use commercially reasonable efforts to develop Auris’s robots in furtherance of the milestones, as measured by the efforts J&J would use for one of its “priority” medical devices. Notably, prior to the acquisition, J&J had been independently developing its own surgical robot. After acquiring Auris, J&J decided to merge the robots into a combined system. The integration process led to complications and delays, and ultimately resulted in failure to achieve certain earn-out milestones.

Following a lengthy trial, the Delaware Court of Chancery found that J&J had breached its commercially reasonable efforts obligations and, more significantly, had committed fraud. The court determined that J&J had deviated from its usual practices in developing the iPlatform device, stating that “[i]t is obvious from the record that J&J’s efforts toward the iPlatform regulatory milestones were not commercially reasonable, as defined in the Merger Agreement.”[15] The court’s fraud finding was based on evidence that J&J had made knowingly false representations during the acquisition process regarding its intentions for Auris’s technology development.

This case also underscores the importance of including mutual disclaimers of reliance on extra-contractual representations in transactions involving earn-outs. These provisions, commonly referred to as “non-reliance” clauses, essentially state that each party is relying solely on the representations and warranties of the other party or parties explicitly set forth in the acquisition agreement, and not on any statements, projections, or assurances made outside the four corners of the contract.

Beyond the fraud and non-reliance issues, the decision also provided important guidance on another frequently debated topic. In a notable (and useful) aspect of the decision, Vice Chancellor Will took the opportunity to clarify a long-debated issue in M&A practice: whether different formulations of “reasonable efforts” create different legal standards. The court stated definitively that “there is no agreement in case law over whether they create different standards. Delaware courts have viewed variations of efforts clauses — particularly those using the term “reasonable” — as largely interchangeable.”[16] This guidance should help practitioners avoid protracted negotiations over whether to use “commercially reasonable efforts,” “reasonable best efforts,” or “all reasonable efforts,” given that, based on the decision in this case, Delaware courts will interpret these standards similarly. As Vice Chancellor Will emphasized, parties should instead focus on “carefully drafting language that delineates the efforts expected of the buyer relative to the achievement of the milestones,”[17] rather than debating which modifier to place before “reasonable.”

|

Lessons from Case Law: Outward-facing vs. Inward-facing Standards

When assessing the feasibility of an outward-facing standard, parties should carefully evaluate whether comparable companies can be reasonably identified. It is crucial to establish upfront if such benchmarks exist. Even then, buyers should be cautious about agreeing to an outward facing standard, as it may limit their flexibility to address unique priorities by requiring them to align with peer practices. If an outward-facing standard is adopted, allegations of the buyer’s insufficient efforts may not suffice to prove a breach without demonstrating a clear deviation from the actions of similar companies under comparable circumstances. Conversely, an “inward facing” standard, which considers the buyer’s own practices, may offer more flexibility but can vary significantly based on the consistency of efforts used by a buyer for its different products and exactly how these bespoke and technical terms are negotiated. |

Additionally, parties should consider the interaction of contractual terms used in earn-out provisions. In Himawan v. Cephalon,[18] the court held that buyer Cephalon did not breach its obligation to use “commercially reasonable efforts” to develop and commercialize a pharmaceutical product so as to achieve certain milestone targets. A key factor in the court’s reasoning was the presence of surrounding language that indicated Cephalon had complete discretion in developing, and obtaining regulatory approvals for, the pharmaceutical product. The court disagreed with plaintiffs’ interpretation that Cephalon was required “to take all reasonable steps to solve problems,” noting that this would be “akin to a best-efforts obligation, under which [Cephalon] must pursue commercialization, through the milestones, at least, unless it would be unreasonable to do so” and would contradict the language providing Cephalon complete discretion.

The court added that the parties could have agreed to a best-efforts clause if they desired.

Himawan v. Cephalon highlights the importance of considering how the language in earn-out provisions works together. Parties should be clear as to whether language contained in the earn-out provisions, taken together, should function similarly to a best-efforts obligation or solely demand good faith action on the part of the buyer.

One alternative to requiring a buyer to use a particular level of efforts to achieve a milestone or maximize an earnout is to provide that a buyer is obligated to spend a specified amount of money to develop a product, conduct regulatory trials or on the other activities the subject of the earnout, and, once those funds have been deployed, the buyer has no further obligations in respect of achieving the milestones or maximizing the earnout. While this approach requires a buyer to spend money, it is an objective standard that avoids the type of scrutiny of a buyer’s conduct that is invariably part of an earnout dispute. If this approach is acceptable to the parties, the buyer will need to negotiate the circumstances in which it will be excused from having to continue to fund the particular activities, including if there are health or safety issues associated with the acquired product, there is a significant challenge to intellectual property used in the acquired product or a competing product comes to market that significantly and adversely affects the projected revenues of the acquired product.

D. Good Faith

Litigation risk in the earn-out context is not limited to claims directly arising out of the purchase agreement but also extra-contractual “good faith” requirements, i.e., sellers claim buyers have breached the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing by taking actions that hinder the attainment of an earn-out, despite not being explicitly prohibited by negative covenants.

Under Delaware law, this implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing is applicable to every contract by operation of law and prohibits parties from engaging in “arbitrary or unreasonable conduct” that prevents the other party from enjoying the benefits of an agreement.[19]

However, this covenant acts only as “a gap-filling function by creating obligations only where the parties to the contract did not anticipate some contingency, and had they thought of it, the parties would have agreed at the time of contracting to create that obligation.” [20] The implied covenant “is not a license to rewrite contractual language just because the plaintiff failed to negotiate for protections that, in hindsight, would have made the contract a better deal.”

Generally, absent express covenants, Delaware case law suggests that buyer actions taken with the primary intent to hinder the achievement of an earn-out, through “dishonest purpose” or “furtive design,” may violate the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing.[21] Other decisions indicate that while the implied covenant prohibits active sabotage of earn-out achievement, it does not require buyers to behave in a way that maximizes earn-out payments when sellers fail to contract for reasonably foreseeable buyer conduct that would do so.

In Retail Pipeline, LLC v. Blue Yonder, Inc., the court explained that absent contractual language to the contrary, a buyer is not generally obligated to operate its business so as to ensure or maximize the seller’s earn-out payments. However, a breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing may occur when the buyer’s conduct demonstrates that it “acted with the intent to deprive the seller of an earn-out payment,” such as by “actively shifting costs into the earn-out period that had no place there.” On the facts of that case, the court denied the seller’s claim because the evidence showed that the parties had discussed, but had not agreed, to require the buyer to make certain efforts that would have increased the chance of achieving the earn-out.

Buyers often negotiate for “sole discretion” to operate the business post-closing but exercising that discretion may then be subject to an ill-defined and unpredictable “good faith” analysis.

Finally, it is important to note that Delaware courts respect parties’ contractual freedom with respect to earn-outs. This affords buyers and sellers significant flexibility to define the applicable duties, covenants, or obligations that will apply during the measurement period. If an acquisition agreement explicitly grants the buyer complete operational control and absolute discretion during the measurement period, no implied covenant liability will be imposed on the buyer if the earn-out conditions are not met due to the buyer’s business operations.[22]

|

Lessons from Case Law: Good Faith

General provisions granting the buyer sole discretion or prohibiting bad faith actions may prove ineffective in preventing post-closing conflicts. If specific actions have been discussed for ensuring or maximizing earn-out payments, relying solely on the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing may be insufficient. The buyer should maintain a record of business justifications for actions taken during the earn-out period that could impact payments. |

E. Acceleration of Earn-out Payments

- In Medal v. Beckett Collectibles,[23] the court denied buyer-defendant Beckett Collectibles, L.L.C.’s motion to dismiss claims that it breached its stock purchase agreement (the “SPA”) with Due Dilly Trilly, Inc. (“DDT”) when it failed to accelerate earn-out payments following the termination of DDT’s founder Andrew Medal’s employment. The dispute centered on whether the language in the SPA required the acceleration of all unpaid milestone payments upon specific events, such as the termination of the founder without cause, and whether the parties were obligated to negotiate in good faith before resorting to litigation. The court found that plaintiff Medal’s interpretation of the stock purchase agreement’s earn-out acceleration clause was reasonable and allowed the case to go forward.

- In negotiating an earn-out, buyers should consider whether it would be useful to them to have a “buy-out” provision, that will allow them to escape restrictions on their ability to conduct an acquired business as they see fit and to realize expected synergies. This could be particularly useful when there is an attenuated earn-out period and, during the course of the earn-out period, a buyer becomes reasonably confident that the earn-out will be payable, in which case, it could agree to pay the full earn-out discounted by an amount that reflects the early payment, in theory, reflecting a “win win” for both seller and buyer.

|

Lessons from Case Law: Acceleration of Earn-out Payments

Language specifying payment acceleration should clearly state whether all earn-out payments or only unpaid earned amounts would be accelerated. According to the SRS 2024 M&A Deal Terms Study, almost 25% of non-life-science transactions that closed between 2014 and 2023 included a provision pursuant to which the earn-out payments accelerated upon a change in control of the target or the holder of the earn-out assets. The Beckett Collectibles transaction discussed above would have benefitted from clearer drafting of its stock purchase agreement’s acceleration provision. Sellers should carefully consider whether termination of employment of key employees engaged in the business the subject of the earn-out should trigger earn-out payment acceleration although buyers should insist that “for cause” termination or resignation without good reason are excluded for purposes of these acceleration provisions. |

F. Expert Determination vs Arbitration

Of course, even with careful planning, a seller that is denied an earn-out payment has an incentive to dispute that denial, and if the parties cannot resolve the issue privately, the seller may seek to do so with the help of independent subject matter experts chosen by the parties, or in court. However, disputes often arise regarding the dispute resolution process itself, in particular as to the role of an independent third party accounting firm versus that of a court or an arbitrator

In Sapp v. Industrial Action Services,[24] Kevin Sapp and Jamie Hopper sold their companies to Industrial Action Services, LLC (“IAS”), a subsidiary of RelaDyne, LLC. The purchase agreement included an earn-out provision, which allowed Sapp and Hopper to receive additional payments if IAS met certain EBITDA benchmarks over three years. Disputes arose when IAS reported that it did not meet these benchmarks, and Sapp and Hopper alleged that IAS intentionally undermined the business to avoid making the earn-out payments. They filed a lawsuit for breach of contract and other claims, while also submitting a “notice of disagreement” regarding the earn-out statement. The District Court initially compelled arbitration, but the Third Circuit Court of Appeals reversed this decision, determining that the parties intended for an accounting firm to resolve specific factual disputes as an expert determination, not through arbitration.

This case highlights the importance of clearly distinguishing between arbitration and expert determination in contractual agreements. The Third Circuit emphasized that arbitration and expert determination are distinct forms of dispute resolution, with arbitration involving a more formal process and broader authority to resolve legal and factual issues, while expert determination is limited to specific factual disputes within the expert’s technical expertise. The court’s decision underscores the necessity for parties to explicitly define the role and scope of the third-party decision-maker to avoid confusion as to who decides what and ensure that the chosen dispute resolution mechanism aligns with the parties’ intentions.

|

Lessons from Case Law: Dispute Resolution

Include a dispute resolution mechanism. The agreement should set for the method and venue for handling any disputes. Arbitration tends to be quicker and more cost effective and include greater confidentiality. However, litigation includes availability of appeal and may alleviate concerns over arbitrator competency or compromise judgements. Clearly define whether the third-party decider is acting as an arbitrator or an expert. Use explicit language such as “acting as an expert, not an arbitrator” to avoid ambiguity. Limit the authority of the expert to specific factual disputes within their technical expertise. For example, specify that the expert’s role is confined to resolving accounting-related issues relating to the calculation of EBITDA, revenues or other financial milestone as applicable, and not broader disputes as to whether the buyer used the requisite level of efforts to achieve the milestone or complied with the applicable covenants regarding the conduct of business during the earn-out period. Limits on Independent Accountant Review: The parties may want to limit what the independent accountant can review to minimize the time and expense of engaging the independent accountant to resolve the dispute. For example, they can limit the independent accountant’s review to: (i) items raised in the objection notice that have not been resolved by the parties and (ii) factual or mathematical errors contained in the information provided to or by the buyer. The parties may also want to have the independent accountant base its decision only on those materials provided to it by the buyer and seller (rather than conducting its own independent investigation). However, if a party believes that these limitations could be disadvantageous, it should consider being silent on this issue in the agreement and negotiating it when a dispute arises. Include or exclude procedural rules to signal the intended dispute resolution process. Arbitration provisions should reference formal procedural rules (e.g., AAA rules), while expert determinations should avoid such references and outline a less formal process. Consider including escalation or mediation provisions, although, generally, not both, as a required preclude to litigation or arbitration, with any escalation or mediation being subject to clear and reasonably short timelines and escalation being to senior executives within each organization who have the authority to quickly resolve a dispute. |

In Bus Air LLC v. Woods,[25] the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware addressed counterclaims brought by the seller relating to the earn-out provision, after which the buyer moved to compel arbitration. The court denied the buyer’s motion and found the parties had not clearly expressed their intent in the purchase agreement to arbitrate all earn-out disputes.

G. Maintaining Good Recordkeeping

Parties planning to include an earn-out provision in their transaction agreement should practice good recordkeeping from the start of negotiations. Maintaining a clear record of how the parties understood the terms of the earn-out at the time of drafting may be crucial in a dispute, especially if the court later finds a contractual term to be ambiguous.

The aforementioned case of Fortis Advisors v. Dematic Corporation illustrates this point. There, the court held that the term “Company Products” was ambiguous and allowed the parties to introduce extrinsic evidence regarding how the products were made, the recommendations of the diligence team at the time of the transaction, and communications between the parties that reflected their understanding of the product at the time of signing.

In another recent case, Schneider Natl. Carriers, Inc. v. Kuntz,[26] the agreement imposed strict constraints on the buyer’s management of the company in an effort to ensure that the company met its earn-out EBITDA targets. One constraint required the buyer to acquire “60 tractors” per year, and if it did not, the seller would receive the full earn-out payment regardless of whether the EBITDA targets were met. The court determined that the requirement was ambiguous because the parties disputed whether the buyer had to simply acquire 60 tractors, or whether it had to grow its fleet of vehicles by 60 tractors per year. The court admitted extrinsic evidence, most crucially the parties’ negotiating history, and after a four-day trial and consideration of almost 300 exhibits, agreed with the seller’s interpretation and required the buyer to make a USD40 million earn-out payment.

In addition to keeping records of negotiations, it is important to keep records of efforts taken in connection with achieving the earn-out milestones. For example, if the buyer is required to use “best efforts” to take a particular action, it is helpful to create a record of what efforts have actually been undertaken.

In addition to the text of the acquisition agreement itself, in the event of ambiguity, one or both parties will seek to include extrinsic evidence evidencing the parties’ intentions regarding the earn-out, including, to the extent applicable (i) a letter of intent; (ii) the confidential information memorandum and notes to financial projections prepared by sellers’ investment bankers; (iii) employees’ recollections of discussions at pre-signing meetings, (iv) pre-signing e-mails among business principals; (v) issues lists and previous drafts of the acquisition agreement and exhibits, including counsel’s redlined document comparison files; (vi) the target’s management presentation to its board of directors, (vii) the target’s Hart-Scott-Rodino Act filings; and (viii) post-closing emails and internal discussions.

|

Lessons from Case Law: Recordkeeping

The parties should remember that courts interpret earn-out provisions not as standalone clauses, but as part of the contract as a whole. In the event of an ambiguous earn-out provision, having a record of business decisions and negotiation of the earn-out provisions, as well as efforts taken to achieve the milestones, is important for proving a case in any future litigation. |

IV. Bridging Valuation Gaps: Earn-Outs and Alternative Approaches.

A variety of tools exist to bridge valuation disparities. This article focused on earn-outs, as they are among the most frequently used mechanisms for reconciling valuation gaps between buyers and sellers. However, parties should thoroughly assess the benefits and risks of using earn-outs, weighing the trade-offs between flexibility and certainty, alignment and conflict, and value and complexity. While earn-outs may help bridge valuation gaps during negotiations, they can also introduce uncertainty, complexity and lead to future disputes. In some cases, like when the valuation gap is relatively small, it might be better to address the difference through upfront compromise to avoid future disputes or litigation.

Alternative approaches to bridge a valuation gap might be considered, depending on the particular circumstances of a given transaction. These options include incentive compensation for carryover executives, or a staggered purchase. These alternatives may come with securities, tax, accounting, benefits and other operational implications, but it is important to remember that an earn-out is not the only way to address value gaps.

[1] See Airborne Health, Inc. v. Squid Soap, LP, 984 A.2d 126 (Del. Ch. 2009).

[2] This article primarily addresses earnout provisions in the context of private M&A transactions. In transactions involving public companies, similar deferred and contingent payment mechanisms are typically structured as Contingent Value Rights (CVRs). While CVRs function substantively like earnouts (by providing for additional payments to sellers based on the occurrence of specified future events or the achievement of certain milestones), they involve additional layers of complexity. Most significantly, depending on the features of particular CVRs, if payable to U.S. persons, they may be characterized as “securities” under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, requiring either registration with the Securities and Exchange Commission or reliance on an available exemption from registration. Additionally, CVRs often require the appointment of a rights agent and the negotiation of a separate CVR agreement, introducing further procedural and administrative complexities.

[3] SRS Acquiom 2023 Life Sciences M&A Study. This represents an average of percentages. Earn-outs were used in a high of 91% of pharmaceutical transactions in 1H 2023.

[4] SRS Acquiom 2025 M&A Deal Terms Study.

[6] SRS Acquiom 2025 M&A Deal Terms Study.

[7] 2023 ABA Private Target Mergers & Acquisitions Deal Points Study (the “2023 ABA Deal Points Study).

[9] See Fortis Advisors, LLC v. Dematic Corp., No. N18C-12-104 AML CCLD, 2022 WL 18359410 (Del. Sup. Ct., 29 December 2022).

[10] See Menn v. ConMed Corp., No. 2017-0137-KSJM, 2022 WL 2387802 (Del. Ch. June 30, 2022).

[11] See Pacira Biosciences, Inc. v. Fortis Advisors LLC, No. 2020-0694-PAF, 2021 WL 4949179 (Del. Ch. Oct. 25, 2021).

[12] See Neurvana Medical, LLC v Balt USA, LLC, No. 2019-0034-KSJM, 2020 WL 949917 (Del. Ch. Feb. 27, 2020).

[13] See S’holder Representative Servs. LLC v. Alexion Pharms., Inc., No. 2020-1069-MTZ, 2024 WL 4052343 (Del. Ch. Sept. 5, 2024).

[14] See Fortis Advisors LLC v. Johnson & Johnson, No. 2020-0881-LWW, 2024 WL 4040387 (Del. Ch. Sept. 4, 2024).

[18] See Himawan v. Cephalon, Inc., 2024 WL 1885560 (Del. Ch. Apr. 30, 2024).

[19] See Winshall v. Viacom Int’l, Inc., 55 A.3d 629 (Del. Ch. Nov. 10, 2011).

[20] See Am. Cap. Acquisition Partners, LLC v. LPL Holdings, Inc., No. 8490-VCG, 2014 WL 354496 (Del. Ch. Feb. 3, 2014).

[21] See O’Tool v. Genmar Holdings, Inc., 387 F.3d 1188 (10th Cir. 2004).

[22] See Collab9, LLC v. En Pointe Techs. Sales, LLC, No. CVN16C12032MMJCCLD, 2019 WL 4454412 (Del. Super. Ct. Sept. 17, 2019).

[23] See Medal v. Beckett Collectibles, LLC, No. 2023-0984-VLM, 2024 WL 3898535 (Del. Ch. Aug. 22, 2024).

[24] Sapp v. Indus. Action Servs., LLC, 75 F. 4th 205 (3d Cir. 2023).

[25] Bus Air, LLC v. Woods, No. CV 19-1435-RGA-CJB, 2022 WL 2666001 (D. Del. July 11, 2022).

[26] Schneider Nat’l Carriers, Inc. v. Kuntz, No. N21C-10-157-PAF, 2022 WL 1222738 (Del. Super. Ct. Apr. 25, 2022).

Distribution channels: Education

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release